Cameron McWhirter is a Winnetka native and a staff reporter for The Wall Street Journal. In 2007, he was awarded a Nieman Fellowship in Journalism at Harvard University where he began work on his first book Red Summer: The Summer of 1919 and the Awakening of Black America. Published in July, this well-researched history chronicles the explosion of race riots and lynchings that followed World War I and shook American cities from Charleston and Washington D.C. to Chicago and Omaha. Both riveting and unsettling, Red Summer traces how this widespread violence gave rise to the NAACP and ultimately set the stage for the civil rights movement. On October 16th Mr. McWhirter visited EPL to read from Red Summer, and as an encore, he recently spoke with us via email about the reaction to his book, the complex causes of 1919’s racial violence, why this important episode in American history has been is so widely forgotten, and what he hopes readers will take away from Red Summer.

Evanston Public Library: First off, congratulations on the incredible reception Red Summer has enjoyed including rave reviews from the Chicago Sun-Times, Booklist, Publishers Weekly, and the Washington Post. What is your reaction to how well your debut book has been received? Have you had any particularly memorable encounters with readers since its July 19th publication?

Cameron McWhirter: Thank you for the kind words. I have given talks around the country and met lots of people, black and white, who did not know about the violence of 1919 or the development of the early civil rights movement. The questions and discussions have been great. I have been impressed by how many Americans are interested in their history and are eager to better understand it. I start the book with a violent episode at a small black church in rural Georgia. On my tour, I have heard from both descendents of whites and blacks killed in that riot. Neither group was angry or bitter. They simply wanted to better understand what happened, and to make sure that it was incorporated into a broader understanding of race relations. A black deacon of that church told me that the ugly episode had been kept in the dark for decades. It was time to turn the lights on, he told me. Readers seem to agree.

EPL: What motivated you to write Red Summer, and when did the idea for the book first strike? Why do you think these pivotal months in civil rights history have largely been forgotten or ignored? As a former Chicagoan and a current Georgian, do you find any regional differences in how the Red Summer of 1919 is remembered?

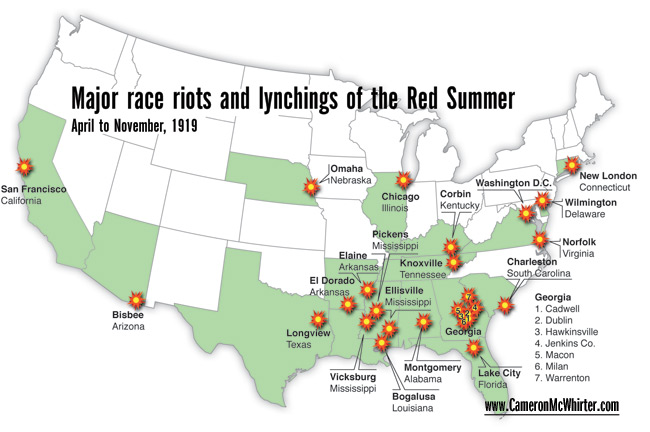

CM: I have been interested in racial violence as an historical phenomenon for years. I encountered ethnic violence in Africa, where I lived and worked during and after college. Back in the U.S., I encountered history of a major race riot in every city where I worked as a reporter. As I researched race riots in American history, I quickly found 1919 to be the apex of anti-black riot and lynching. Yet no one knew much about it. In Chicago, few people know about the riot that swept the South Side and paralyzed the city. In Georgia, where I know live, I also found a collective amnesia regarding 1919. The same is true in Washington, D.C., Texas, Tennessee, Nebraska and other places where the Red Summer violence broke out. Events move so rapidly through our lives that important history can quickly be forgotten, even though past events shape who we are today. Restoring the Red Summer of 1919 into the public consciousness was one of my objectives in writing the book.

CM: I have been interested in racial violence as an historical phenomenon for years. I encountered ethnic violence in Africa, where I lived and worked during and after college. Back in the U.S., I encountered history of a major race riot in every city where I worked as a reporter. As I researched race riots in American history, I quickly found 1919 to be the apex of anti-black riot and lynching. Yet no one knew much about it. In Chicago, few people know about the riot that swept the South Side and paralyzed the city. In Georgia, where I know live, I also found a collective amnesia regarding 1919. The same is true in Washington, D.C., Texas, Tennessee, Nebraska and other places where the Red Summer violence broke out. Events move so rapidly through our lives that important history can quickly be forgotten, even though past events shape who we are today. Restoring the Red Summer of 1919 into the public consciousness was one of my objectives in writing the book.

EPL: Could you give us a sense of the research that was required to write Red Summer? What were some of the challenges you encountered, and did your years as a journalist help you overcome them? What role did libraries play in your research process?

CM: The greatest challenge in my research was that many of the violent episodes were never fully explored by government agencies or reported by local media. Only some of the cases stemming from the violence made it to court. Piecing together what happened was difficult. Also, the people involved have all died, and participants in the riots were reluctant to recount their actions in memoirs or letters. But thanks to amazing research collections in libraries around the country (including in Chicago), I was able to piece together the Red Summer. Academic libraries were essential, especially those at Yale, Emory, Harvard, Columbia and the University of Chicago.

EPL: What were some of the major factors and events that led to the storm of racial violence in 1919? How did some of these same factors sow the seeds for the future civil rights movement?

CM: These issues are explored extensively in the book, but in brief, the year 1919 was a year of chaos and uncertainty (much like today). Americans were unnerved by a poor economy, strikes, anarchists, communists and general world mayhem. Within this context, three things occurred involving African Americans that were actually good for black people. But because they were happening in a context of general panic, they became flashpoints for anti-black violence. One phenomenon was black soldiers serving in World War One. They had fought bravely and were treated well by the French people. Their officers and others told them they were fighting for democracy. But when they returned home, they found whites, especially in small towns in the South, angry that blacks appeared to be trying to assert equality. Another phenomenon was the great migration. The number of black people migrating north increased dramatically during the war as northern industry turned to cheap labor from the South since foreign immigration ceased. As more black, nonunion labor arrived in factories and shops in the north, friction intensified. Finally black sharecroppers, the quintessentially downtrodden class in American society, actually made money in 1919 because cotton prices were extraordinarily high. With extra cash, sharecroppers bought land, cars, fancy clothes and other items, angering whites. The bottom line: blacks were leaving their pre-war social positions as secondary citizens, and this caused a violent white reaction. Importantly, the violence had the opposite effect of what was intended. Blacks fought back literally, legally and politically on a level not seen in decades. That response laid the groundwork for the later civil rights movement.

The NAACP awakened in 1919 – doubling membership, expanding circulation of The Crisis, holding major rallies, holding a large anti-lynching conference in New York, forging a small coalition of supporters in Congress, etc. It was not the end of anti-black violence, Jim Crow, segregation and other racial problems. But it was the beginning of the decades-long effort to achieve racial equality in this country.

EPL: What do you hope readers will to take away from Red Summer? Can you suggest additional books or resources for those interested in learning more about this time in American history?

CM: First, I want readers to understand that these riots and lynchings occurred and why they took place. Then I would like them to see that the modern movement for black civil rights has a much longer history than most people realize. More broadly, Americans need to understand race if they want to understand American history. Race weaves throughout our nation’s story, beginning when blacks first were brought here as slaves in 1619 (three centuries before the Red Summer). Read Alexis de Tocqueville. He’s writing about the racial situation in the 1830s. Take this section from Democracy in America: “In almost all the states where slavery has been abolished, voting rights have been granted to the Negro, but, if he comes forward to vote, he risks his life. He is able to complain of oppression but he will find only whites among the judges. Although the law makes him eligible for jury service, prejudice wards him off from applying. His son is excluded from the school where the sons of Europeans come to be educated….Thus, the Negro is free but is able to share neither the rights, pleasures, work, pains, nor even the grave with the man to whom he has been declared equal…”

Those lines could have been written in 1919 or after Reconstruction or during Jim Crow. If you want to understand American history, you need to understand how our nation has dealt with racial and ethnic divisiveness.

EPL: What are your plans now that Red Summer has been published? Do you have any new projects in the works? Can we look forward to another book sometime in the future?

CM: I am quite busy as a reporter for The Wall Street Journal, but I have begun work on a biographical project that shows great promise.

Interview by Russell Johnson