Silk Road Rising is a Chicago theatre company founded in 2002 with the mission of “telling stories through primarily Asian American and Middle Eastern American lenses.” On Monday, February 8th at 7 pm, they join EPL in sponsoring the lecture “Shakespeare in the Middle East” featuring the former Syrian Minister of Culture and award-winning author Riad Ismat. One of six February programs planned as part of #DiscoverWill: Illinois Libraries Celebrate Shakespeare’s First Folio, “Shakespeare in the Middle East” will explore the lengthy performance history of the Bard’s work in the region and how it connects today to a broader Middle Eastern audience. In anticipation of this fascinating program, we recently spoke via email with Silk Road Rising’s Founding Artistic Director Jamil Khoury about the company’s 2007 adaptation of The Merchant of Venice and the challenges of translating Shakespeare for a non-Christian, Arabic-speaking audience.

Silk Road Rising is a Chicago theatre company founded in 2002 with the mission of “telling stories through primarily Asian American and Middle Eastern American lenses.” On Monday, February 8th at 7 pm, they join EPL in sponsoring the lecture “Shakespeare in the Middle East” featuring the former Syrian Minister of Culture and award-winning author Riad Ismat. One of six February programs planned as part of #DiscoverWill: Illinois Libraries Celebrate Shakespeare’s First Folio, “Shakespeare in the Middle East” will explore the lengthy performance history of the Bard’s work in the region and how it connects today to a broader Middle Eastern audience. In anticipation of this fascinating program, we recently spoke via email with Silk Road Rising’s Founding Artistic Director Jamil Khoury about the company’s 2007 adaptation of The Merchant of Venice and the challenges of translating Shakespeare for a non-Christian, Arabic-speaking audience.

Evanston Public Library: In 2007, Silk Road Rising staged a masterful re-working of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice set among Hindu and Muslim immigrants living along Venice Boulevard in modern day Los Angeles. Why do you think this adaptation to a non-Anglo cultural context worked so well?

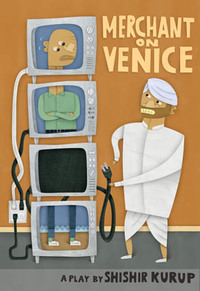

Jamil Khoury: I believe that what Shishir Kurup created with Merchant on Venice was a stroke of artistic genius! He wrote the play in iambic pentameter, aligning modern vernacular with Shakespearean rhythms, infused it with Bollywood references, and transferred a historically contentious relationship between Christians and Jews onto a complicated contemporary relationship between Hindus and Muslims. The Jewish Shylock became The Muslim Sharuk, albeit this time, in a more egalitarian, less incriminating vein. Diaspora and the “new world” may have become the fresh setting, but the unsettled scores of “back home” remained as vivid and colorful as ever. In the end, a pound of flesh is still for the asking, and “do we need bleed” remains the impassioned query.

Let it be known that in no way am I an expert on the works of Shakespeare, but clearly the richness of his characters, the complexity of their relationships, and the conflicts that divide them create a theatrical landscape that is remarkably mobile. The fact that so many cultures see their own stories in the stories of Shakespeare is testimony to the undeniable universality of the struggles and deceptions, desires and betrayals, yearnings and surprises that punctuate his dramas. Shakespeare doesn’t adapt the world, the world adapts him, and in so doing, discovers truths and realities entirely unknown to Elizabethan England. Where there’s conflict – be it ethnic, religious, gendered, or otherwise – there’s a Shakespearean adaptation just waiting to be born.

Let it be known that in no way am I an expert on the works of Shakespeare, but clearly the richness of his characters, the complexity of their relationships, and the conflicts that divide them create a theatrical landscape that is remarkably mobile. The fact that so many cultures see their own stories in the stories of Shakespeare is testimony to the undeniable universality of the struggles and deceptions, desires and betrayals, yearnings and surprises that punctuate his dramas. Shakespeare doesn’t adapt the world, the world adapts him, and in so doing, discovers truths and realities entirely unknown to Elizabethan England. Where there’s conflict – be it ethnic, religious, gendered, or otherwise – there’s a Shakespearean adaptation just waiting to be born.

EPL: Although few of Shakespeare’s plays have overtly religious themes (other than perhaps Measure for Measure or The Merchant of Venice), they were written and performed by and for a uniformly Christian audience struggling with the fallout of the Protestant Reformation. How does this Christian sensibility translate to the largely non-Christian Middle East?

JK: Great question! I actually think the Christian sensibility that lives in Shakespeare’s work – be it subtlety, implicitly, or overtly – has huge relevance to today’s largely non-Christian Middle East (not to discount the cultural importance of Middle Eastern Christians, which is considerable). Questions of faith, fear of God, religion as a form of social control, the power of clergy, manipulation of sacred texts as a pretext for seizing and maintaining power, and the role of dogma in determining one’s actions were all factors informing the Bard’s lived reality and his contextual universe. Certainly when we investigate abuses committed in the name of religion, rivalries within and between traditions, and the blending of religious and political authority, we see phenomena that manifest themselves across cultures and histories with resounding frequency. Forgive me for either trivializing or sounding cliche, but the contemporary Middle East – with its myriad of challenges and struggles – translates quite seamlessly onto a Shakespearean stage. Whether the divides are secularist vs. Islamist, Sunni vs. Shi’a, Israeli vs. Palestinian, tribal vs. universalist, feminist vs. traditionalist, or states vs. movements, the battles that raged within Europe and Western Christendom in the 16th and 17th centuries, many of which are still being fought today, bear a great deal of resemblance to any number of conflicts raging around our world, including some in the United States.

EPL: Shakespeare’s influence is not only literary but linguistic. He created hundreds of words and phrases still in popular usage. Is it possible to adequately translate these plays into Arabic and retain their full power?

JK: I’m neither an Arabic linguist nor a scholar of Elizabethan English (modern American English is my native tongue, my command of written and spoken Arabic is fair to decent), but what excites me about this question is that poetry and the artistic uses of language play such an important role in Arab cultural production. So while literal translations of Shakespeare’s plays into Arabic may not do justice to the rich, complicated, and oftentimes humorous meanings of his words, I’m going to imagine that talented translators have great fun finding analogous and allegorical words and phrases that resonate with Arab audiences. The aesthetics of Shakespearean language align quite beautifully with the aesthetics of Arabic poetry and musical lyricism. Both rely heavily on metaphors, puns, double entendres, riddles, hidden meanings, and camouflaged language. The power incumbent to these plays is not lost-in-translation, albeit some of the Bard’s intended meanings will change, and the contextualization of his plays in either historic or contemporary Arab settings introduces new meanings and stakes as well. I don’t know if the same holds true for German or Hindi or Mandarin, but I can say with full confidence that dramaturgically speaking, Arabic is Shakespeare’s friend!