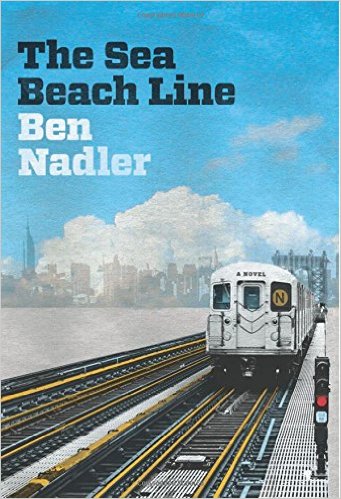

Ben Nadler believes that “a writer owes a reader a good story,” and with his excellent new novel The Sea Beach Line, that’s exactly what the Brooklyn-based author delivers. A hypnotic hybrid of literary crime fiction and Jewish folklore, The Sea Beach Line tells the gripping coming-of-age story of Izzy Edel, a young man adrift after being expelled from Oberlin for hallucinogenic drug use. Given renewed purpose after receiving a mysterious postcard from his estranged father Alojzy, Izzy travels to New York City where he must navigate Alojzy’s world of street vendors, gangsters, and members of a religious sect as he searches for his missing dad. Filled with sharp insights on loyalty, self-reliance, and the complicated bonds of family, The Sea Beach Line was described in Library Journal’s starred review as “a mesmerizing narrative that will speak to any readers who have tried to make sense of their parents’ lives or the secrets that people keep.” This Monday, April 25th at 7 pm, you can hear Nadler read from The Sea Beach Line when he visits Bookends & Beginnings as part of an EPL-sponsored event also featuring author Abby Geni. In anticipation of his visit, we recently spoke with him via email about literary traditions, his novel’s origins, the history of Hasidic tales, collective memory, and a few of his favorite books and poems.

Ben Nadler believes that “a writer owes a reader a good story,” and with his excellent new novel The Sea Beach Line, that’s exactly what the Brooklyn-based author delivers. A hypnotic hybrid of literary crime fiction and Jewish folklore, The Sea Beach Line tells the gripping coming-of-age story of Izzy Edel, a young man adrift after being expelled from Oberlin for hallucinogenic drug use. Given renewed purpose after receiving a mysterious postcard from his estranged father Alojzy, Izzy travels to New York City where he must navigate Alojzy’s world of street vendors, gangsters, and members of a religious sect as he searches for his missing dad. Filled with sharp insights on loyalty, self-reliance, and the complicated bonds of family, The Sea Beach Line was described in Library Journal’s starred review as “a mesmerizing narrative that will speak to any readers who have tried to make sense of their parents’ lives or the secrets that people keep.” This Monday, April 25th at 7 pm, you can hear Nadler read from The Sea Beach Line when he visits Bookends & Beginnings as part of an EPL-sponsored event also featuring author Abby Geni. In anticipation of his visit, we recently spoke with him via email about literary traditions, his novel’s origins, the history of Hasidic tales, collective memory, and a few of his favorite books and poems.

Evanston Public Library: The Sea Beach Line has been favorably compared to the work of Paul Auster, John Steinbeck, and Michael Chabon and celebrated as a wonderfully unique blend of literary fiction, noir, and Jewish folklore. How does it feel being compared to such talented authors? Do you see The Sea Beach Line as fitting into any certain genres more than others? Do you think it even matters?

Ben Nadler: Honestly, those comparisons feel incredibly daunting. But I think of these affinities less in terms of genre, than tradition. Steinbeck wrote about American labor—what it meant to do hard work in America in his era, and what kind of rewards that did or did not bring. So I hope I am picking up on that tradition, in some manner.

This overlaps with the tradition of street novels, noir novels, hardboiled crime novels. Dashiell Hammett had a Marxist understanding of his novels as part of a tradition of working people’s literature, even if he turned around and disparaged his work for that same reason. So absolutely, I’m working in the tradition of Hammett, Jim Thompson, David Goodis from Philadelphia, Nelson Algren in Chicago. More recently, Walter Mosley.

And my book wouldn’t exist without the rich tradition of Jewish American fiction, which in turn draws on traditions of Yiddish literature, Jewish folklore, and scripture. I couldn’t have written my book without reading, and reacting to (or against), I.B. Singer, Saul Bellow, Henry Roth, Delmore Schwartz, Grace Paley, and so many others.

EPL: Could you give us some insight into your inspiration for The Sea Beach Line? Where did the idea for the book originate, and how did it evolve over time? As a former Manhattan street vendor, how much of the novel’s West Fourth Street bookselling scene was drawn from personal experience?

EPL: Could you give us some insight into your inspiration for The Sea Beach Line? Where did the idea for the book originate, and how did it evolve over time? As a former Manhattan street vendor, how much of the novel’s West Fourth Street bookselling scene was drawn from personal experience?

BN: The idea for the novel definitely came from being a bookseller on the street in Manhattan, about a decade ago. I always knew there was a book in their somewhere, but I needed some distance before I could figure out how to write about.

That’s just the setting, though. I think the next element that came into play was the character of Alojzy. I had this idea of a larger than life character—a street legend, someone who lived more in myth than factual reality—who had disappeared from the street. But once I had a missing character, I needed someone to search for him. So the absent father led me to my seeker, the searching son, Izzy.

As the book evolved, it became more plot-driven. It was originally much dreamier, focused around the setting, characters, and interwoven tales. All of that stayed, but the plot became more tight, detailed, and logical, as I tried to figure out how Izzy’s search really functioned, on a practical level. This is where it’s important to have a good editor, to keep you on track when you veer too far away from the plot, into the dream world.

EPL: Jewish history and folklore figure prominently in the novel. Can you discuss the traditional purpose of Hasidic tales as well as their role in your book? Do you think readers who are less familiar with Jewish traditions can still connect with the story?

BN: Hasidism was a religious movement in the Pale (the part of Eastern Europe where Jews lived, including present day Poland and Ukraine), starting in the 1700s. Learned, legalistic rabbis in urban centers like Vilnius had strong connections to, and understandings of, Judaism, but a lot of poor Jews out in shtetels were spiritually alienated from it. So Hasidism was this mass movement, meant to bring a mystical, ecstatic, immediate experience of Judaism to all these Jews. It pretty quickly congealed into something much more structured and less romantic, but that was the idea.

Because a lot of this demographic wasn’t able (for reasons of time, money, and education) to engage in traditional rigorous scriptural study, Hasidic rabbis used oral tales, in vernacular Yiddish, to connect with them, and teach them things. (Talmud is full of tales already, so this wasn’t a sacrilegious or strange innovation.) For people from other faith traditions, vague analogs to Hasidic tales might include the sermons of Protestant circuit riding preachers, or the tales of Sufi masters.

A lot of these Hasidic tales were about rabbis and their students, because they had a heuristic goal. But then a guy named Rebbe Nachman blew this open, by talking about princesses and turkeys and stuff instead. This is still a living tradition—I have heard Hasidic tales about things that happened in Brooklyn in the ’80s and ’90s. I think that’s part of how Hasidic tales function in my book, the old tales and tropes from Eastern Europe tumble forward into contemporary New York. There’s no solid delineation between these times and spaces. And the malleability of this narrative tradition allows for that.

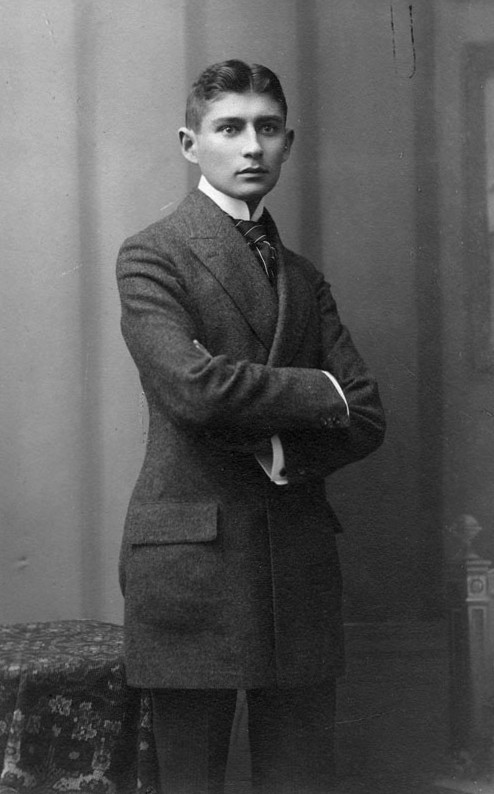

I personally really first encountered the tradition of Hasidic tales through studying Franz Kafka. I wanted to know where this man’s work had come from. And in a lot of ways, it turns out it came from the Belz Hasidic tradition, from the Breslov Hasidic tradition. He added a new energy to it, he had his own vision, and he wasn’t beholden to a religious community, but he drew on that tradition. So that’s also part of what I’m doing in my book, honoring Hasidic tale as a literary form and tool, not just a religious tradition.

But no, I don’t think my novel is just for Jewish readers, or readers familiar with Judaism. The past couple weeks, I have been teaching James Baldwin’s works to one of my classes. A student from a southern, African American, Pentecostal tradition was able to provide some insight into the religious practice in Go Tell It on the Mountain which I would never have otherwise understood. On the one hand, this did enrich my understanding of the “Prayers of the Saints” chapters. But the same time, my lack of specific knowledge of the function of tarry services has never prevented me from connecting to Baldwin’s characters.

EPL: Can you discuss how collective memory influences Izzy’s search for his father Alojzy? How do the recollections of his mother, sister Becca, and Alojzy’s various street associates shape how Izzy thinks of his missing dad? How do these memories affect Izzy’s search for himself?

BN: Well, this is another way Hasidic tale, or folklore more broadly, plays into the novel. Alojzy is the central character—more so than Izzy—but he really only exists for the reader through tale. Izzy recounts tales in his own memory, and he collects oral tales gathered from other of Alojzy’s friends, enemies, colleagues, ex-girlfriends. Becca and Ruth, Izzy’s sister and mother, are reluctant to engage in this oral tradition, but they give their stories too. And like with Hasidic tales, Izzy takes these tales of Alojzy instructionally. He uses them to determine where he should go to look for his father, and how he should act to live up to the model set by his father.

EPL: While The Sea Beach Line nimbly explores complex questions involving loyalty, self-reliance, and the complicated bonds of family, it is also a gritty, thrilling mystery. What is it about crime fiction that attracts you as a writer? At the end of the day, would you rather your readers be enlightened or entertained?

BN: There has been some debate by reviewers if my book is “crime fiction” or “literary fiction.” Either one works for me. I love the crime fiction world. My first ever published short story was in Thuglit, a crime fiction magazine which remains one of my favorite lit mags.

Fiction, in general, allows a way to approach vital question we don’t have the language to otherwise. Crime fiction addresses a specific set of questions that arise throughout life: Why did a person have to die? Is a person innocent or guilty? What is one person’s responsibility to another person? This crime fiction tradition, grappling with these questions, includes the hardboiled guys I listed above, it includes Sherlock Holmes and other Victorian stuff, and really, it goes back to Genesis, where Cain commits a murder, then tries to hide the crime when God interrogates him.

But also, crime fiction is a great structure for pushing plot forward, because there are very clearly stated questions, and the reader will come along with you to see how they are answered. I’m not sure it is within my purview—or power—as a fiction writer to enlighten anybody. I do think a writer owes a reader a good story.

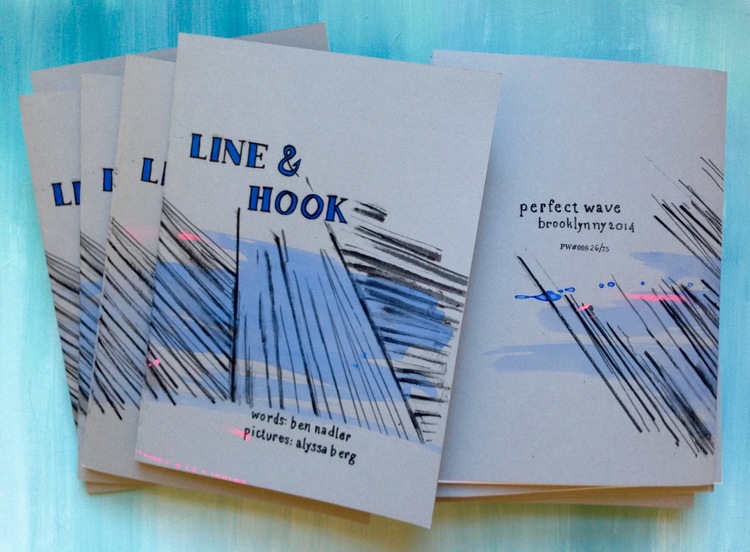

EPL: Can you give EPL readers a sense of what you’re working on next? Can we look forward to a new novel sometime soon? Recently you partnered with artist Alyssa Berg on the poetry and comic chapbook Line & Hook. Do you have any other collaborative projects in the works?

BN: I don’t have any collaborative projects in the works at the moment, but I love working with visual artists, and hope to do more of that. I believe Alyssa is working on her own full length graphic novel these days, though hopefully she and I will do something else together in the future.

For my part, it’ll be a little while before there’s a new novel. I’m just working on some essays and stories right now. It’s interesting to try to write a succinct short story after writing such a long novel. Scale changes things.

EPL: Can you recommend any books you’ve read lately? Seeing as it’s National Poetry Month, can you share a favorite poem to help us celebrate?

BN: I’ve been reading a lot of nonfiction recently. I’m currently finishing up A History of Reading by Alberto Manguel, which is a fascinating book. I imagine a lot of library patrons will be interested in the subject matter.

The last novel I enjoyed reading was Relief Map, by my old friend Rosalie Knecht. It came out in March. A strong evocation of a small town. The experience of the outsider in town, a refugee from the Republic of Georgia, is especially interesting.

I have so many favorite poems, but I’ll mention a few:

I’ll start with some relatively recent stuff: There is a contemporary Hasidic poet named Yehoshua November who wrote a beautiful poem called “Baal Teshuvas at the Mikvah.” Saeed Jones has some great poems in his book Prelude to a Bruise. I traded Joanna C. Valente a copy of my novel for a copy of her The Gods Are Dead, one of the better deals I’ve ever made.

I’ll start with some relatively recent stuff: There is a contemporary Hasidic poet named Yehoshua November who wrote a beautiful poem called “Baal Teshuvas at the Mikvah.” Saeed Jones has some great poems in his book Prelude to a Bruise. I traded Joanna C. Valente a copy of my novel for a copy of her The Gods Are Dead, one of the better deals I’ve ever made.

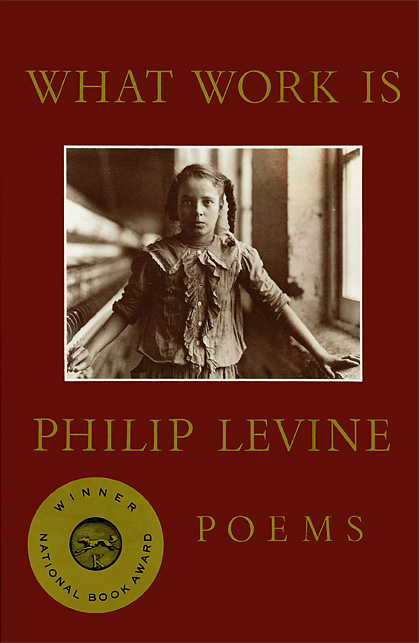

Coming back to the Midwest for a visit, I often think of d.a. levy, who did a lot in a short time. “New Year” is one of my favorite of his. Another great Midwestern poet was Phil Levine. I had the pleasure of seeing him read before he died, and I’d recommend his books, such as What Work Is, to anyone.

One of my favorite poems across the years has been “Valediction” by Sherman Alexie. It’s a surprisingly formal poem—couplets, iambic pentameter, all of that–but it speaks very urgently and directly to a common feeling of grief and helplessness. I’ve had to send it to a few friends, when I thought it would help them. Maybe someone reading this interview needs it now.

Valediction by Sherman Alexie

I know, I know, I know, I know, I know

That I could not have convinced you of this,

But these dark times are just like those dark times.

Yes, my sad acquaintance, each dark time is

Indistinguishable from the other dark times.

Yesterday is as relentless as tomorrow.

There is no relief to be found in this,

But, please, “Yours is not the worst of sorrows.”

Chekhov wrote that. He meant it as comfort

And I mean it as comfort, too, but why

Should you believe us? You didn’t believe us.

You killed yourself because your last dark time

Was the worst, I guess, of many dark times.

None of my verse could have saved your life.

You were a stranger. You were dark and brief.

And I am humbled by the size of your grief.

Interview by Russell J.