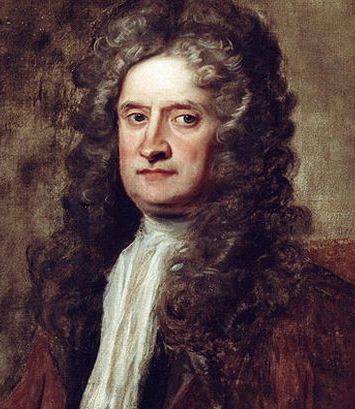

Dr. Michelle M. Wright is an Associate Professor of African American Studies at Northwestern University and the author of the forthcoming book The Physics of Blackness: Rethinking the African Diaspora in the Postwar Era. On Tuesday, October 8th, she will discuss her new book and related topics when she visits EPL’s 1st Floor Community Meeting Room at 7 p.m. as part of the Evanston Northwestern Humanities Lecture Series. Titled “Blackness When You Least Expect It: Understanding Racial Diversity in the 21st Century,” Dr. Wright’s lecture will center on what it means to be “Black” and how Sir Isaac Newton’s laws of motion and gravity influence our modern understanding of race. In anticipation of her visit, we recently spoke with her via email about the practical problems of undefined “Blackness”, the Middle Passage, Newton, identity as performance, and equality amidst diversity.

Dr. Michelle M. Wright is an Associate Professor of African American Studies at Northwestern University and the author of the forthcoming book The Physics of Blackness: Rethinking the African Diaspora in the Postwar Era. On Tuesday, October 8th, she will discuss her new book and related topics when she visits EPL’s 1st Floor Community Meeting Room at 7 p.m. as part of the Evanston Northwestern Humanities Lecture Series. Titled “Blackness When You Least Expect It: Understanding Racial Diversity in the 21st Century,” Dr. Wright’s lecture will center on what it means to be “Black” and how Sir Isaac Newton’s laws of motion and gravity influence our modern understanding of race. In anticipation of her visit, we recently spoke with her via email about the practical problems of undefined “Blackness”, the Middle Passage, Newton, identity as performance, and equality amidst diversity.

Evanston Public Library: In the introduction to The Physics of Blackness, you write that even though it has been big business for centuries “Blackness” has remained both “undefined and suffering under the weight of many definitions.” Could you discuss the many practical problems this has caused? What factors are driving the newfound urgency to more accurately define what it means to be “Black”?

Michelle Wright: While Blackness has never been a homogenous identity, it is becoming even more diverse now: many African Americans are quite literally that—African American, but African American Studies and census records on Blacks in the U.S. tend to overlook these differences. Studies come out claiming certain properties to Blackness—inferior genetics, or a likelihood for incarceration, a hostility towards education, and so forth—even though this is not only not true for all Black people, it is not even true for most of them. As a result, our scholarly research, scientific research, our health initiatives and state policies are becoming increasingly inaccurate because they cling to a set of stereotypes that fail to take in the ethnic, national, linguistic, ancestral, social, economic, political and sexual diversity that informs Black identities not only in the United States but across the globe because Black communities and individuals reside in almost every nation there is. We are pouring hundreds of millions of dollars and hundreds of thousands of working hours into myths.

EPL: You write extensively about how the U.S. anchors its definition of “Blackness” in the Atlantic slave trade, or Middle Passage. Could you detail the shortcomings of this common understanding?

MW: There is a relatively new movement that has arisen in the past few years that has taken on the name “post Black”. It has been met with a great deal of hostility, I think, because it is misunderstood as rejecting the importance of slavery to contemporary “Middle Passage” African American identities (the “Middle Passage” was the name given to the route taken by slave ships from West Africa to the Americas). Yet when I read blogs, books, editorials, and so forth by those who advocate a “post Black” outlook, what I read is the desire for a broader definition of Blackness that does not exclude slavery but instead includes all of the events, histories, ideas, breakthroughs and consciousness with which Black people intersect. “Middle Passage” Blacks are not simply the descendants of slaves; when we insist upon that definition (or that definition is placed upon us) it radically limits our political vision and creative output, to say the least. It takes us out of the category of human and reduces us to a symbol of oppression. As a result, students educated in the West are usually unaware of the role Blacks played in major historical events such as the Revolutionary War, or the two World Wars. We even have scholars who theorize how Blacks have been the victims of Western progress, failing to recognize that Blacks have been part of Western history and its breakthroughs before there was even a “West”.

EPL: In your excellent essay “Postwar Blackness and the World of Europe,” you explore the idea of “Blackness” through the enlarged lens of World War II and its aftermath. How does this viewpoint affect the Middle Passage narrative?

MW: World War II was truly a world war with a global influence that continues to this day, but most books, films and references to it make it seem as if only white Americans, Russians, Europeans, and some Japanese were part of it. One way to break ourselves out of this misguided notion that the only part of history relevant to Black people is when we were oppressed by whites and how we fought back is to take the large, important, historical moments and show how in fact we were not just passive participants but an active part of it. What most historians fail to acknowledge about World War I and II, for example, was that an early part of European mobilization was conscripting men from their colonies into service because they realized that they could not win a war without colonial forces. The Triple Entente victory in World War I was directly due to the use of colonial forces, which was why the Italians, French and British deprived Germany of its colonies in the Treaty of Versailles, and why they ran first to their colonies when Hitler made clear he intended to take Germany into yet another war.

EPL: How do Sir Isaac Newton’s laws of motion and gravity influence our modern day understanding of race?

MW: Without necessarily realizing it, all of us base our assumptions about time on Newton’s laws of motion and gravity—the argument that an object in motion stays in motion until stopped or sped up by another object, to put it crudely. This notion of time was borrowed by white European and U.S. philosophers, and mistranslated as proof that time moves “forward” in line. We see timelines, chronologies and this assumption of progress in so many different ways every day it rarely occurs to us that linear progress is not a fact. Whatever it is we do, we do not make it incrementally better each day, and the history of the world is not a progressive line forward from the primitive lands of Black Africa to the civilized nations of the white West. Yet we tend to think of it this way—that white bodies symbolize progress, and Black bodies are “closer to nature” because they are somehow less civilized.

EPL: Could you discuss the idea that identity is performance? How does this concept influence what it means to be “Black”?

MW: We often think of racial identities as physical—you’re Black because you either “look” Black or you have “Black DNA”. But there is no physical or biological basis for Blackness. You can’t tell if someone is Black from their DNA, and we also know that all Black people don’t look alike. Some can “pass” for white, Asian, Middle Eastern, and so on for the simple reason that Blackness is an invented identity placed on Black Africans b

y white Europeans as far back as the 15th century. Blackness, in other words, is not a “thing” or a “what”, but a “when” and a “where”—an identity that was a glimmer of a myth in Europe in the 15th century, and one which has grown and expanded globally since.

Blackness happens when we realize it, when we think it, and any identity based in time (when) and space (where) is a performance. That doesn’t mean it’s fake, superficial, “not real”, or even that the performer controls it –it means that it is always shifting and very complex, always interacting with a real or imagined audience. If I go into a bar and have trouble getting served, I might first assume it’s because I am Black. Then say I notice all the patrons, unlike me, are dressed casually—and there are some Black folks among them. Realizing this will likely change my performance for the bartender. I might remove my jacket, lean against the bar a bit, chat with someone, and so forth—I drop my intended racial performance and pick up another. Because I don’t speak in a way perceived as stereotypically Black, when I am calling customer service and hear someone who “sounds Black” on the line, I will deliberately change my tone a little in the hope that they will hear a more “Black” pronunciation—and then who knows? They might cut me some slack for having messed up the form I was meant to fill out and take a few minutes to guide me in completing it correctly. Blackness is not something I am, but something I do.

EPL: You write in its introduction that you see The Physics of Blackness as part of the greater debate over how we define and establish equality in the midst of diversity. Could you discuss the complexities of this debate as you see them?

MW: If asked, many of us would say that we are all for human equality, but I don’t think any one of us would be able to explain how we achieve this equality when every single one of us is different from the other. Even families, as we famously know, don’t always get along, and they grew up together! This problem of achieving equality in the face of diversity becomes feasible if we understand difference as something that is performed and always shifting, changing from moment to moment. That means that difference can be fleeting. Equality between different people can take place in certain moments of performance and that becomes a potentially productive moment for exchange and engagement. It is those moments we should focus on when we need to move together. Before we leap off into pretending that some people are superior to others, we need to recognize superiority as a performance—the math whiz may be completely incapable of making a simple repair to a clock radio—rather than something “hard wired” into our DNA.

EPL: What do you hope patrons will to take away from your October 8th lecture “Blackness When You Least Expect It?” Can you suggest additional books or resources for those interested in learning more?

EPL: What do you hope patrons will to take away from your October 8th lecture “Blackness When You Least Expect It?” Can you suggest additional books or resources for those interested in learning more?

MW: I am hoping people leave wanting to think more about these issues, and that when they come across a news item or T.V. program that discusses racial, gender, sexual, class, or some other kind of difference, they’ll engage with it and question it. If the new program asserts that Black communities bear the most violence, perhaps they will ask if this factoid applies to all Black communities (it won’t) across all space and time (it won’t). Then perhaps they will ask what kinds of violence are being assumed. After all, wealthy communities are also violent, but the beatings, the rape, the abuse, takes place behind closed doors in a privacy that benefits the perpetrator, quite often all the way through the police investigation and trial. At the end of the day, we need to recognize that most of the media is more intent on entertaining us rather than informing us, meaning they will not look at events as a complex occurrence in space and time but instead frame it “typical” or “atypical” behavior for the people, person, or community involved.

As far as I am aware, no-one else is talking about identities created as an effect of space and time, but I would recommend Post Black: How a New Generation is Redefining African American Identity by Chicago’s own Ytasha Womack, and From Eternity to Here by Sean Carroll, which is a very readable exploration of the puzzle of time and how it continues to defy easy characterization.

Interview by Russell J.