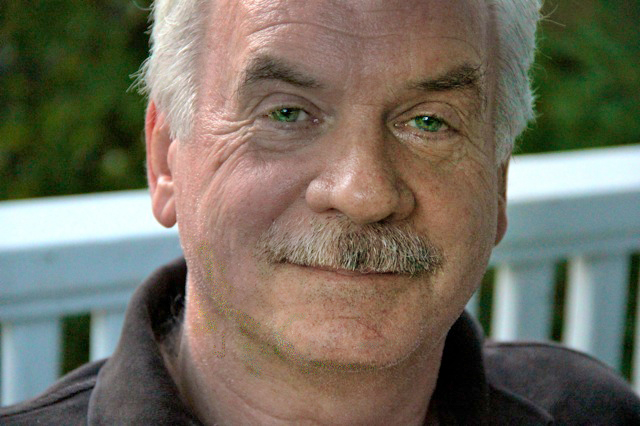

Patrick Shiplett is an Evanston artist who is the latest to be featured in our ongoing exhibition series Local Art @ EPL. A cartoonist whose work has appeared in the Chicago Tribune, NY Times, and Washington Post, Shiplett’s exhibit features nearly three dozen cartoons he presented to the New Yorker’s editorial staff before they explained “there was no room for a cartoonist [his] age in their lineup.” Titled Too Old for the New Yorker, Shiplett’s cartoon collection is currently on display on the 2nd floor of EPL’s Main Library where you can catch it through August 31st along with selected writing from his blog. You can find more of his cartoons and writing by visiting his website, and we recently spoke with him via email about his artistic origins, pitch meetings at the New Yorker, advice for aspiring cartoonists, and his blog.

Evanston Public Library: Can you tell us a little about your background as a cartoonist? Was there something specific in your life that sparked a need to create? What drove you in the beginning, and what drives you now?

Patrick Shiplett: My mother would clear the dining room table, spread newspapers around and leave me alone to draw and paint. My father would come by and encourage me. I pored over the correspondence-course art books my sister-in-law passed on. I didn’t know what I doing, and my work was bad. But the desire to improve held my interest for hours and the slightest recognition was enough to keep me going.

My affair with cartooning came much later. It evolved from my career as an advertising art director and copywriter. I retired with all the muscles needed by a cartoonist.

EPL: Can you give us a window into your creative process? Where do you get your ideas, and how much time do you spend on each cartoon from conception to completion?

PS: I attended a two-year commercial art academy. A man named Pop ran the small 60-student, non-accredited school. Tough and opinionated and Texan, Pop demanded that we fill page after page with “thumbnails” — small squares with rough squiggly drawings representing a visual and a headline for a print ad. That process has never failed me.

Some cartoons come easily. Others fight you for years. The ones you struggle with, that you doubt and rework to the point you want to abandon them, are often the ones people like the best. It’s important to humor your stupidest ideas. You have to trust that epiphanies will come. Then you’ll wonder how such obvious and elegant answers have eluded you for so long. Being clueless is a prerequisite for being creative.

EPL: Can you share more about your experiences with the New Yorker, and describe the process of submitting your work? What were your meetings like with the editorial staff?

PS: What I can tell you is that it was a wonderful adventure. Even though I’m a published political cartoonist, I knew that becoming a New Yorker cartoonist was a fantasy on par with playing in the NFL or orbiting the earth on a NASA mission. But hey, I’d end up with a portfolio of cartoons and a world-class pastrami sandwich if nothing else.

After sending in scores of cartoons by mail, an illustrator friend told me about the weekly pitch sessions at the New Yorker’s offices which are just off Times Square. I flew to New York, uninvited, twice within a nine-month period. I met one-on-one with the cartoon editor Bob Mankoff. In our first meeting Bob was enthusiastic, saying that I was among the small number of wannabes who have the creative skill-set he looked for. He gave me his email and recommended that I keep submitting. However Bob, who’s a year older than me, took deliberate pains to warn me that younger cartoonists are tireless and hungry.

During our second meeting it became clear he had been trying to scare me off — to avoid the risks of telling me I was too old to be considered. I appreciate that Bob had the grace to confirm that my age, not my cartoons, was the problem.

EPL: Do you have any advice for aspiring cartoonists?

PS: Cartooning is great fun, but you have to take it seriously. Give yourself plenty of time to hone your writing and drawing skills. You’ll need them both. Even the simplest, childlike drawing style requires a confident touch. Have a cup of coffee and enjoy the process for itself.

Cartoons are born of incongruent ideas so pay attention to whatever odd observations go through your head. Daydream whenever possible. And it helps to read, read, read— you get to think using other peoples’ minds.

Once you’ve developed a portfolio you’ll want to be published. Do serious research about the different outlets for your kind of cartoon work. My first cartoon was published in my high-school year book. We all have to begin somewhere.

EPL: What motivated you to start your blog? More specifically, what inspired your features “Out Among Humans Notebook” and “People at a Coffee Shop?”

PS: The “Out Among Humans” notebook is a collection of short, single-cell essays. There’s a fault line between the staggering abilities of our species on one side, and our vanities and foibles on the other. Those raw contradictions are what make the human animal worth writing and reading about. We are something, aren’t we?

A number of my posts deal with people at The Brothers K coffee shop in Evanston. The place is a social petri dish where you can observe scientists, artists, entrepreneurs, ministers, scholars and ordinary folks from all over the world. There’s something special in the air here. It’s the scent of people.

EPL: Finally, what do you hope people will take away from your exhibit?

PS: I’m flattered that Evanston Public Library has mounted a month-long, one-person show of my work. If a guest at EPL spends a few moments looking at the things I’ve put up, and feels the time was well spent, well then I’ve done my job.

Interview by Russell J.