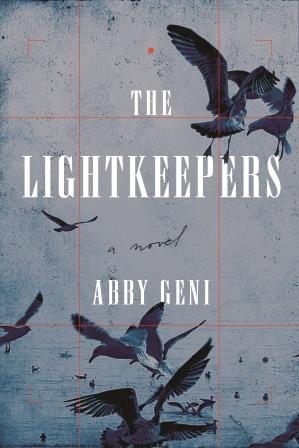

Abby Geni insists she’s “always been a novelist at heart,” and with her provocative debut thriller The Lightkeepers, it’s clear the Evanston native is following her true calling. Part murder mystery, part ghost story, The Lightkeepers tells the twisting tale of nature photographer Miranda as she begins a one-year residency on the Farallon Islands – a remote, untamed archipelago off the California coast. Shortly after arriving, Miranda is assaulted by one of the six biologists studying the islands, and when her attacker is found mysteriously dead days later, she must struggle to face the reality of her assault as the violence escalates around her and suspicions run wild. An insightful exploration of the nature of recovery and the harsh indifference of the natural world, The Lightkeepers was described by the Chicago Tribune as both “an accessible page-turner” and “an astonishingly ambitious debut [that] like many literary classics… raises questions about humanity that are anything but light.” Back on April 25, Geni visited Bookends & Beginnings to read from The Lightkeepers as part of an EPL-sponsored event also featuring author Ben Nadler. If you missed her that night, however, have no fear because we recently spoke to her via email about her novel’s origins, bringing the Farallon Islands to life, and the human disconnect with nature.

Abby Geni insists she’s “always been a novelist at heart,” and with her provocative debut thriller The Lightkeepers, it’s clear the Evanston native is following her true calling. Part murder mystery, part ghost story, The Lightkeepers tells the twisting tale of nature photographer Miranda as she begins a one-year residency on the Farallon Islands – a remote, untamed archipelago off the California coast. Shortly after arriving, Miranda is assaulted by one of the six biologists studying the islands, and when her attacker is found mysteriously dead days later, she must struggle to face the reality of her assault as the violence escalates around her and suspicions run wild. An insightful exploration of the nature of recovery and the harsh indifference of the natural world, The Lightkeepers was described by the Chicago Tribune as both “an accessible page-turner” and “an astonishingly ambitious debut [that] like many literary classics… raises questions about humanity that are anything but light.” Back on April 25, Geni visited Bookends & Beginnings to read from The Lightkeepers as part of an EPL-sponsored event also featuring author Ben Nadler. If you missed her that night, however, have no fear because we recently spoke to her via email about her novel’s origins, bringing the Farallon Islands to life, and the human disconnect with nature.

Evanston Public Library: First off, congratulations on the wonderful critical praise The Lightkeepers has earned including starred reviews from Publisher’s Weekly, Booklist, and Kirkus. What is your reaction to how well the novel has been received? How does it feel to be described as a “master storyteller” by Publisher’s Weekly?

Abby Geni: It’s remarkable! I wasn’t expecting anything of the kind. My first book, The Last Animal, was a short story collection, and though it got some nice reviews, short story collections tend to land with much less splash than novels do. I’ve been delighted by the critical reception The Lightkeepers has received. It’s always nice to have someone tell you that you’re a “master storyteller,” since there are many days during the active creation phase of a new project during which you don’t feel like a master of anything.

EPL: Could you give us a window into your writing process for The Lightkeepers? Where did the idea for the novel originate? How much of the book was pre-planned, and how did it evolve over time?

AG: The idea for the novel arrived from a few different places. To begin with, I encountered Susan Casey’s wonderful memoir, The Devil’s Teeth, in which she talks about her visit to the Farallon Islands. I was captivated by the location and struck by the marvelous, dangerous, fascinating plethora of marine life to be found there. In general, I love to incorporate nature into my writing, so I let the idea of the Farallon Islands simmer on the back burner of my brain for a while. It seemed like an ideal setting for a story.

Then I became interested in mysteries as a genre – Agatha Christie, Dorothy Sayers, Georgette Heyer – and I was struck by how perfectly structured those stories can be. A good mystery has a perfect architecture of plot in which absolutely nothing is wasted or extraneous. I was gearing up to try writing my first novel, and I found comfort in the idea of building a mystery structure inside the book. My favorite mysteries are the ones with a suspicious death, an enclosed setting, and a limited number of suspects. The Farallon Islands absolutely fit the bill. Soon I realized that I had the structure I wanted and the setting I wanted, and from those elements, the novel was born.

EPL: How did the experience of writing a novel compare to working on your story collection The Last Animal? Do you prefer one form over the other?

AG: I think I’ve always been a novelist at heart. But only recently have I practiced enough as a writer and grown enough as a human being that I feel ready to write something so long and complex. I loved working on The Last Animal, but a part of why I was able to write short stories was that I wrote the collection around a theme – the interaction between human beings and the natural world – which made it feel as though the stories were all part of something larger. From now on, I believe I will mostly work on novels, with the occasional short story written in between as a palate cleanser between the longer stories that come more naturally to me as an author.

EPL: You bring the Farallon Islands so completely to life in The Lightkeepers that they are a distinct character as much as the novel’s setting. Kirkus in particular raved about your “unmatched ability to describe nature in ways that feel both photographically accurate and emotionally resonant.” What so attracts you to nature as a writer? Have you ever visited the Farallon Islands, and if not, can you tell us about your research? How were you able to render them so vividly?

AG: First of all, thank you! Secondly, I had Susan Casey’s memoir, which is full of vibrant detail and also includes a map of the islands, which was invaluable. I did a ton of additional research, gathering photographs to guide my visual imagery and keeping track of which animals would be present during each season of the year that Miranda, my main character, would be on the islands. I love to write about places I haven’t been to, since I relish the process of doing research but I hate to travel, so writing about a place like the Farallon Islands allows me to visit in my mind without ever having to leave my comfortable, familiar home.

During the writing process of any new book, I like to do a good amount of research – enough that I feel comfortably grounded in fact – but also leave a certain amount of detail unknown, which allows me to fill in some of the world with my imagination. This process of mental rendering brings the place to life in my mind to a remarkable extent. I have never been to the Farallon Islands, but I feel that I lived there the whole time I was creating The Lightkeepers, and I miss the place now that the writing process is done.

EPL: In a 2013 Publishers Weekly interview you said, “One of the great illusions of the human experience is that we are somehow outside of nature – beyond the food chain – that we are not animals ourselves.” Can you discuss how you challenge that illusion in The Lightkeepers? How do Miranda and the biologists resemble the animals they observe and record?

AG: It’s something I’m often aware of in my daily life: the disconnect between human beings and the natural world, and how that disconnect informs – and sometimes harms – us. It’s a part of why I incorporate nature into my writing so often. I’m fascinated and horrified by climate change, and I believe that some of why we’ve let things get so bad is because we don’t really believe that change to the climate and change to the planet and trouble for the planet will ultimately affect us as a species. Human beings feel so detached from nature that we can see something awful happening to the polar bears, the oceans, or the rain forests, and it doesn’t feel immediate or vital.

So I write about animals and nature as much as I can, and I draw parallels between human beings and animals as much as I can. Without giving too much of the ending of The Lightkeepers away, I wanted to show that there isn’t much difference between humans and whales or birds or sharks. Regardless of what we may tell ourselves, we’re all animals in the end.

EPL: Miranda believes that “trauma and pain are the foundations of art” and that, when faced with trauma, a photographer is “an artist first, a human being afterward.” Do you share her views on the relationship between art and pain? How does Miranda initially use photography to avoid facing her pain, and how does it ultimately help her begin to reconnect with her humanity?

AG: I initially wanted Miranda to be a nature photographer as device to get her to the Farallon Islands. The other residents are biologists, but I wanted Miranda to be a bit of an outsider, so I didn’t want her to share their passion for science. So initially I came to the idea of photography less as a philosophical or character-based choice and more of a simple mechanism to fuel the plot.

However, Miranda’s work quickly became much more vital to her nature than I had anticipated. I tend to find my characters through their passions. To find out more about my characters, I like to research what they know. In The Lightkeepers, Mick is a seal specialist, so I researched pinnipeds to learn about who he was. Galen and Forest are shark specialists, so I researched sharks to learn about who those characters were. And I researched photography to learn more about who Miranda might be.

However, Miranda’s work quickly became much more vital to her nature than I had anticipated. I tend to find my characters through their passions. To find out more about my characters, I like to research what they know. In The Lightkeepers, Mick is a seal specialist, so I researched pinnipeds to learn about who he was. Galen and Forest are shark specialists, so I researched sharks to learn about who those characters were. And I researched photography to learn more about who Miranda might be.

I was astonished at how the study of photography informed my understanding of her. I don’t know if I share her views on the link between art and pain, but I do believe that she initially distances herself from humanity by standing on the other side of the camera from the world around her. She finally reconnects with humanity by putting herself in the frame instead. Once she sees herself on film, she begins to see herself – and the world around her, and so much more – clearly at last.

EPL: Can you give EPL readers a sense of what you’re working on next? Can we look forward to another story collection sometime soon? Do you have any ideas brewing for a second novel?

AG: I’m deep into a first draft of a new novel. I don’t know when it’ll become a real printed book, instead of a story that exists somewhere between my brain and the computer, but I’m loving every minute of creating something new. And that’s all I’ll say. Elizabeth McCracken, a terrific author and one of my teachers at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop, told me that there are times when you have to “protect the dream of the book,” and I’m still at the stage when I’m ferociously protective of my burgeoning dream-story.

EPL: Can you give us a window into what you like to read? Can you share any good titles you’ve recently enjoyed?

AG: Sadly, I find it hard to read in the same genre that I’m writing. Since I write literary fiction, this means that I don’t often read literary fiction, which is frustrating for me. But I love nonfiction, science fiction, and mysteries, so that sustains me. At the moment, I’m working my way through the Golden Age of Mysteries. I highly recommend Dorothy Sayers! I can’t say enough good things about her work.

Interview by Russell J.