While theater lovers know Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams as two great pillars of 20th century American playwriting, most are surprised to learn of their enormous popularity on the Syrian theater scene. On Wednesday, February 1st at 7 pm, the award-winning Syrian dramatist and director Riad Ismat visits EPL for “Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams in Damascus” – a lecture cosponsored by the Chicago theater company Silk Road Rising during which Ismat will share his experiences adapting Miller and Williams for Arab audiences. In anticipation of this fascinating program, we recently spoke via email with Mr. Ismat and Silk Road Rising’s Founding Artistic Director Jamil Khoury about how The Glass Menagerie, A Streetcar Named Desire, and All My Sons resonate in Syria, Ismat’s Austrian meeting with Arthur Miller, and “how great art can transcend and bridge cultural and political differences.”

Evanston Public Library: When did the plays of Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller first appear on the Damascus theater scene? How did Arab audiences initially respond to them?

Riad Ismat: Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman enjoyed a staging by the Damascus National Theater (DNT) in the early 1970s. The first of Williams’ plays to be produced by DNT was The Glass Menagerie in 1964. It was reproduced in the early 1970s by the Syrian Ministry of Education, and I directed it as graduation production for the Academy of Dramatic Arts in 1999. Shortly before that in 1998, I adapted and directed A Streetcar Named Desire for DNT which was a big challenge due to the popularity of Elia Kazan’s film. The productions of Streetcar and The Glass Menagerie both enjoyed great success, though, especially among university students.

Jamil Khoury: I remember in the mid-1980’s, while studying Arabic in Damascus, that I was told by some university students who were majoring in English literature that they were fans of Williams and Miller. These Syrian students, none of whom had ever visited the United States, were quite passionate and sophisticated in their analyses of such plays as All My Sons, Death of a Salesman, A Streetcar Named Desire, and The Glass Menagerie. They related to these stories on very personal levels and quite seamlessly transported them to Syrian families and environments. There was nothing “foreign” or “exotic” in these narratives for them, but instead a striking familiarity and immediacy. I was both surprised and not at all surprised. I also couldn’t help but think that while so many English literature departments in the United States ignore plays (focusing instead on novels, short stories, and poetry), in Syrian universities plays and dramatic literature were thoroughly integrated as part of the curriculum.

Evanston Public Library: Mr. Ismat, how have Williams and Miller influenced your work as a director and playwright?

Riad Ismay: Not very much in my beginnings as a playwright, but certainly, a lot after I adapted and directed some of their plays. Over time I have grown to appreciate more and more the dramatic depth of these two great pillars of American drama. Recently, I’ve written some original plays inspired by their characterizations.

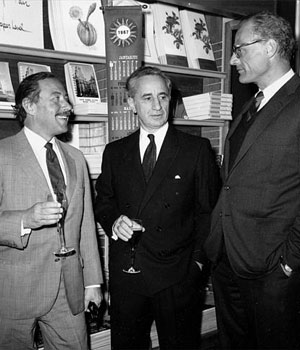

In 1996, I met Arthur Miller personally in Salzburg, Austria. We had several conversations over the course of a week, and I attended rehearsals for his Death of a Salesman by the National Theater in London. I expressed to Mr. Miller my wish to adapt and direct his play The Crucible. He seemed positive and pleased after hearing how I had adapted Streetcar to base it in Damascus in the 1950s. I still wish to direct The Crucible because it’s an allegorical play about witch hunting, a synonym of the repression of innocent citizens in my region. It’s said that the accused are “innocent until proven guilty.” In my part of the world the accused are “guilty until proven innocent.”

Evanston Public Library: Mr. Khoury, how have Williams and Miller influenced Silk Road Rising productions? Does the company have any future plans to stage one of their respective plays?

Jamil Khoury: Silk Road Rising showcases playwrights of Asian and Middle Eastern backgrounds who create protagonists of said backgrounds. The plays of Williams and Miller do not fall within our mission. The majority of playwrights we work with are Americans of Silk Road heritage, typically immigrants and the children of immigrants. As theatre artists and theatre aficionados, they are inevitably exposed to and influenced by these two masters. Some playwrights we’ve worked with have spoken of Williams and Miller as “mentors” and “inspirations.” Others have adapted Williams’ and Miller’s work into cultural contexts of their own. Interestingly, we are currently considering one such adaptation for our next season. Stay tuned!

Evanston Public Library: What do you hope people will take away from your program “Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams in Damascus” on February 1?

Jamil Khoury: An appreciation for the universality of Williams’ and Miller’s plays. Insights into contemporary Arab theatre and stories that resonate with Arab audiences. An understanding of how great art can transcend and bridge cultural and political differences. For too long, the United States and the Arab World have been perceived as “polar opposites,” forever locked in a contentious, civilizational battle. Hopefully this program will illuminate for people just how futile and wrong those perceptions are.

Riad Ismat: I want the American audience to hear about how meaningful and valuable the plays of Williams and Miller are in Syria and the Arabic culture. Their works are enjoyed universality and have proven to be immortal like the works of Shakespeare, Ibsen, Chekhov, and O’Neil. They cross the geographical barriers between cultures and address human souls everywhere and at any time.

Interview by Russell J.