Black History Month is here. For many libraries and bookstores, this means pulling together large displays of black authors, black subject matter, black history, etc. But as many have pointed out, this month often turns out to be the only time these books are ever highlighted. Indeed some libraries and bookstores outright refuse to create these displays, opting instead to create them for the eleven other months of the year.

Here at the Evanston library we strive to keep our displays diverse 365 days of the year. Meanwhile, I’ve been dealing with a different issue. If you’ve seen our Adult Fiction section then you know that it’s a good sized collection. Periodically we remove the titles that haven’t circulated in 4+ years, to make room for newer titles. I handle this weeding personally, making exceptions for any book that I feel is important to have in the collection. And inevitably what I come across are amazing books by black writers. These books are titles that often did not have the publicity push other books were granted. As a result, we buy them, but they disappear into our stacks, never to be read again. The solution? Why not make a display of them?

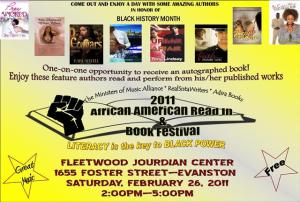

I thought about postponing the display until March, so as to make a point about doing them all year, but then I saw this sign:

That pretty much summed up the books I wanted to display. Note the part on the bottom that says, “Read them EVERY month – not just in February.”

Here then are some titles that you may not have heard about, but that are definitely worth discovering. I’ll include the professional reviews for each one:

If Sons, Then Heirs by Lorene Cary

From Publishers Weekly, “Cary tells a complex story of family, race, and the challenges of reconciling the present with a persistent past. Alonzo Rayne was raised in South Carolina by his great-grandmother, Selma. Now he owns a construction business in Philadelphia and lives with Lillie, a single mom, and her seven-year-old son, Khalil. As the story begins, Khalil accompanies Alonzo to South Carolina where Alonzo urges the aging Selma to sell her land so they can pay for her long-term care. But she hasn’t owned the land since King, her husband, died almost 50 years ago; Selma was King’s second wife, not an heir, and this unforeseen fact, combined with ancient, racist inheritance laws, makes for a sticky situation. And Alonzo’s mother suddenly wanting to reconnect after years of abandonment further complicates matters; her marriage to the white man she met after abandoning her son turned her life around. Finally, Alonzo’s investigation into his great-grandmother’s land puts him on a collision course with the men who brought about his great-grandfather’s violent end. Cary (Black Ice) pairs generations of loving, and loyal individuals with social history, making for an absorbing and moving tale.”

Hottentot Venus by Barbara Chase-Riboud

From Publishers Weekly, “In 1810, Sarah Baartman sailed willingly from her home in South Africa to England with her English husband, believing that fame awaited her as an African dancing queen. Well, she certainly found fame. Based on the true story of a woman who was exhibited as part of a freak show in London’s Piccadilly and upon her death at age 27 was publicly dissected in France, this novel by poet, sculptor and novelist Chase-Riboud (Sally Hemings) conveys Sarah’s victimization so well that the reader is still cringing after the last page is turned. Sarah herself copes with the harsh reality of her husband’s betrayal-she’s essentially been sold into slavery-through denial and gin. Her best chance to escape comes when abolitionist Robert Wedderburn intervenes by bringing her contract before a judge in an attempt to rescue her. Sarah, however, won’t go along with it, because she doesn’t want to return to Good Hope, where her Khoekhoe tribe struggles against colonization. Wedderburn captures the reader’s frustration when he tells Sarah: “You are the unwitting collaborator of your own exploitation, agent of your own dehumanization!” Indeed, there are many tough scenes to endure, as Europeans endlessly ridicule her body and elongated genitals (mutilated as part of a tribal ritual) and examine her as a scientific curiosity. What makes the story, and Sarah’s life, more bearable are the tender scenes with Alice, Sarah’s English governess who stays with her and truly cares for her. Kudos to Chase-Riboud for exploring this story of oppression and for humanizing a woman who was virtually regarded as an animal, according to the ideology of the day.”

Unfinished Masterpiece by Anita Scott Coleman

From Publishers Weekly, “Coleman (1890–1960) was a black woman born in Mexico and raised in the American Southwest. Her connection to the Harlem Renaissance is mostly temporal, but that doesn’t detract from this book’s appeal. The 21 short stories it gathers, arranged chronologically, grow more somber and complex over time. “Rich Man, Poor Man—” features a white rancher’s daughter falling for a black chauffeur: it’s typical of the early group (published 1919–1922) in its domestic plot, happy ending and tangential treatment of race. The tenor shifts in the 10 stories of 1926–1933: the women are fallen or falling; secrets (a slave past, passing) tumble out; an antiblack riot erupts at the center of “The Brat.” Things get very ominous in “Cross Crossings Cautiously,” when a five-year-old white girl asks a black man to the circus, and off they go. Coleman’s perspective extends and challenges conventional notions about the settings, characters and themes of early 20th-century African-American fiction. Her work is entertaining for the general reader and historically significant for the scholar.”

Johnny Mad Dog by Emmanuel Boundzeki Dongala

From Library Journal, “Taking place during a West African civil war, this powerful novel by Dongala (Little Boys Come from the Stars) centers on two members of rival ethnic groups caught up in the chaos. Johnny Mad Dog is the teenage commander of a small militia unit gorging itself on killing and looting. Laokole, a 16-year-old who dreams of becoming an architect, has been her family’s caretaker since a previous conflict left her father dead and mother crippled. Forced from their home by looting, Laokol‚ and her remaining family join hoards of refugees, going first to the UN compound and then to a jungle village. Finally, with her mother dead and brother vanished, Laokol‚ ends up in a refugee camp. Here, her life intersects fatefully with that of Johnny Mad Dog. Dongala is sharply critical of the hypocrisy of those from different ethnic groups who slaughter one another for personal gain yet pose as freedom fighters to the Western powers, which in turn protect their own citizens while ignoring the carnage. Hope hangs by a tenuous thread in this violent yet compelling tale.”