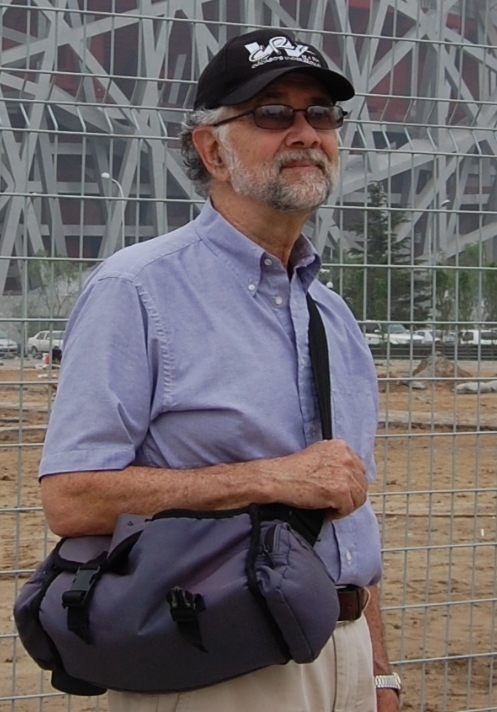

David Pritchett is an Evanston educator and photographer who made his Local Art @ EPL debut with the 2015 exhibit “Daily China.” Now through January 31, he’s back on the 2nd floor of EPL’s Main Library with “On the Job” – a striking series of color photographs exploring working life in Nigeria, Wales, England, Saudi Arabia, and China. Captured between 1964 and 2016, Pritchett’s fascinating images record farmers, entertainers, shop keepers, and sailors while examining how “work exists in all times, countries, and cultures.” Off the Shelf recently spoke with Mr. Pritchett via email about the challenges of shooting in different countries, how he connects with his subjects, capturing a Nigerian snake handler on film, and what he hopes people will learn from “On the Job.”

David Pritchett is an Evanston educator and photographer who made his Local Art @ EPL debut with the 2015 exhibit “Daily China.” Now through January 31, he’s back on the 2nd floor of EPL’s Main Library with “On the Job” – a striking series of color photographs exploring working life in Nigeria, Wales, England, Saudi Arabia, and China. Captured between 1964 and 2016, Pritchett’s fascinating images record farmers, entertainers, shop keepers, and sailors while examining how “work exists in all times, countries, and cultures.” Off the Shelf recently spoke with Mr. Pritchett via email about the challenges of shooting in different countries, how he connects with his subjects, capturing a Nigerian snake handler on film, and what he hopes people will learn from “On the Job.”

Evanston Public Library: Back in 2015 you made your Local Art @ EPL debut with your series “Daily China” before returning this month with “On the Job.” Do you see any connections between your two shows?

David Pritchett: The connection between “Daily China” and “On The Job” is that when we look at others there are no others. That paraphrases a Buddhist concept, and is not original with me.

EPL: For “On the Job,” you shot in Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, England, and China over the span of 50 years. What has so inspired you to photograph working life all over the world? Did you encounter any challenges unique to shooting in the different countries you visited?

DP: Simplistic as it sounds, my work in social contexts and surroundings so different from my own ignited and keeps aflame my desire to understand what I see and the surroundings in which I witness. I’ve used some images in teaching my American students, but mostly I was acquiring a personal record that has become an extensive archive. Never persistent in journaling, I use a camera to record and preserve my experiences.

When I point a camera in some settings, subjects freeze or pose creating a more stiff, though authentic, image. In others, photography itself may be considered invasive so I exercise patience and circumspection before shooting. In most cases I ask, get permission, and shoot. Without permission or under cultural restrictions, I leave my camera in my backpack, then watch and listen.

EPL: Generally speaking, did you form connections with your subjects? How did you go about doing so? Can you describe any instances when you thought it was better not to take a photograph?

DP: In some cases subjects wanted to be photographed, especially those who were performing or demonstrating a personal skill. When one offers to take a photo of someone working, there is an act of validation going on. Photos are a powerful medium, and most of us like to be preserved in photos at our work places, with our tasks, and with our work mates. In other circumstances, I had become a part of the surrounding community and was not an unusual presence with a camera.

In Muslim contexts – Northern Nigeria, Saudi Arabia and the Emirates – I was aware of social conventions and worked within them, never trespassing. In Saudi Arabia, I was invited with my wife to join women weavers in visiting their work place and sharing sweet tea and coffee. In a shaded yard we were shown the processes of shearing goat hair, weaving in ground looms, and finishing rugs and camel bags. None of the women were veiled as I was non-Muslim and not harram (forbidden) to see their faces. However, it would have been unacceptable for me to take photos of the unveiled women. My cameras stayed in my backpack, those rich images now imprinted only in my memory. I always respected taboos regarding nudity, death, burial, sacrifice, prayer, modesty, and propriety thereby avoiding pushing the cultural envelope without permission just to get an image.

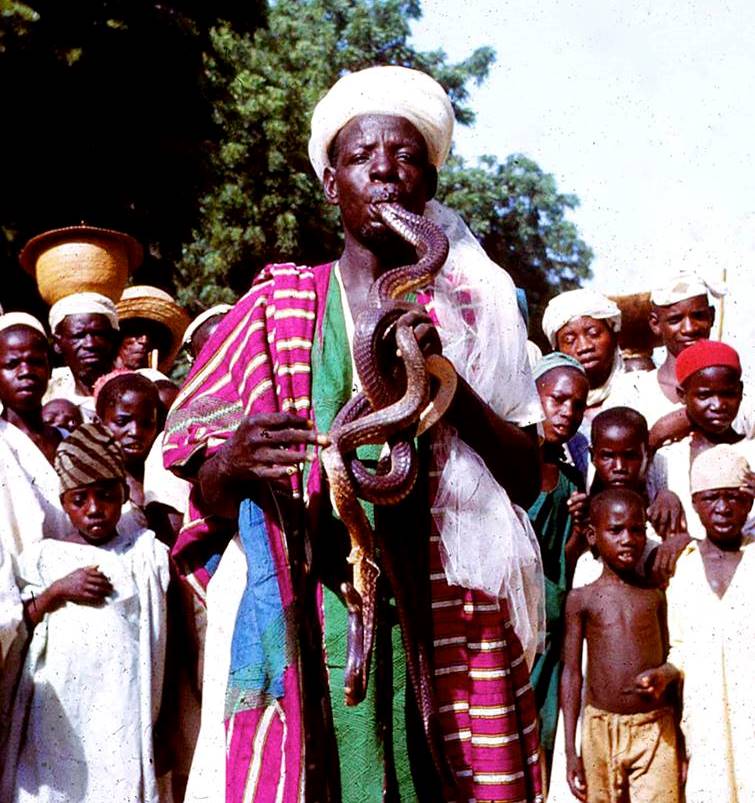

EPL: Could you tell us the stories behind the your striking photographs of the Nigerian snake handler or the train conductor in North Wales? How did each photo reveal itself?

DP: In 1965 during a school holiday, two Peace Corp teachers and I got part-time jobs assisting a UNFAO (United Nations Farm and Agriculture Organization) team which was working a land tenure project in Sokoto, Northern Nigeria. During our two week assignment, we attended two Friday markets which were held after prayers. Markets were filled with local crafts, some manufactured products, and food supplies. There were also entertainers like the snake handler or a young man with a chained hyena who performed for “dash” – whatever an observer wished to give for the privilege of watching. I gestured to the snake handler that I wanted to take photos, which he acknowledged. When I finished, I gestured a “thank you” and started to walk away. He became stern faced and walked toward me with two snakes in one hand and an upturned palm. I got his meaning, dug for the change in my pocket, and placed it in his hand. He accepted, and we parted without me personally meeting the snakes.

The train conductor was a “target of opportunity” image I took at a popular steam rail tourist attraction in Porthmadog, Wales. He was a volunteer during the summer tourist season, dressed in a period costume, but holding another day job.

EPL: What do you hope people will take away from “On the Job?”

DP: I hope the photos – though captioned to provide some context – will coalesce around the idea of the universality and dignity of common, and some truly uncommon, work.

EPL: Are you currently working on any new projects or preparing for any future shows? Where can we find more of your work after your EPL show closes?

DP: I am working on three new projects, as yet untitled, focusing on structures, machines, and settings in which people live. I have been posting this exhibition on my Facebook pages, accessible with my name, David Pritchett.